By MaryAnn Zima

Our son, John, was born 10 days late in the spring of 1990, healthy and robust but with a very worried expression on his face.� Doctors said everything was fine, and he was two days old when we went home to our family. Shortly after we settled in, he began having problems breathing and started coughing, so I called the weekend pediatric nurses. They all thought my baby�s inability to get enough oxygen was just normal adjustment.�

By the time I realized how wrong they were, we were rushing through the ER doors, the sweet newborn in my arms now in full cardiac and respiratory arrest. He was what they call a Code Blue.�

I watched people in white coats and scrubs running in from all directions. I had once worked in that hospital, and knew exactly what it meant when they ran like that. I also understood that no matter what happened next, everything about our future had just changed.��

After what felt like years waiting outside the trauma room, a doctor came out to tell us that Johnny was alive, but had been born with a heart defect of a severe sort � the kind you can�t live with. They transferred him to a private room in the ICU since his condition was so fragile, and I now understood why this tiny boy had been so worried the moment he arrived.�

Johnny made it through that night and within a few days, the staff began working on a plan.� With some artful rearrangement of vessels, children born with the kinds of heart defects that used to be 100% fatal were getting a shot at growing up.

His condition required open-heart surgery in which they connected vessels, created shunts and opened ventricles. It was spectacularly complicated and took nearly all day to accomplish; that is why they only hire superheroes for this work.

When we got the call that Johnny was back in ICU, we were directed not to the private room he�d been in before, but to a big, open area where there were lots of eyes and ears. It had one nurse for each of the beds, which were separated by a big equipment bay that powers the stork�s nest of pipes and wires and tubes and EKG leads and catheters and IV fluids and meds for each patient. It�s pretty amazing how they can get all that into a tiny seven-pound person, but they do, although they need a full-sized bed to lay it all out on.

We quickly noticed that Johnny had a shivery kind of tic going on, which our nurse recognized as an ICU stress response to having one�s body so thoroughly invaded, as well as being in a place where the lights never go out and the noises and voices never go quiet. Even under sedation, he was so very stressed. Some quiet music, I thought, might help our baby relax.�

At home, I collected his sister�s Fisher-Price tape player and a handful of cassette tapes, picking out some soft Bach, chamber pieces, classical guitar � whatever seemed right for the job. With the music playing near his head, Johnny slept through the night, so I played the tapes whenever I was there.��

Once, as I was getting ready to leave for the day, the nurse at the little girl�s bedside next door asked if she could keep the music playing, because it was calming her patient too. I showed her how it worked, where new batteries went if they were needed, and thought how great it was to have a musical twofer happening.

Around the end of the week, Johnny was strong enough to be sent to the cardiology floor. As we gathered up the things that needed to be transferred with him from the ICU, our nurse quietly told me, �You know, normally we use paralytic drugs to help these babies lie still when they�re recovering from such huge surgeries.��

She said the little boy at the end of our row, still unconscious, was being weaned off fentanyl, an effective but addictive narcotic.� �That music you brought here kept Johnny so calm he never needed the narcotics. In fact, it kept all of us calm.�

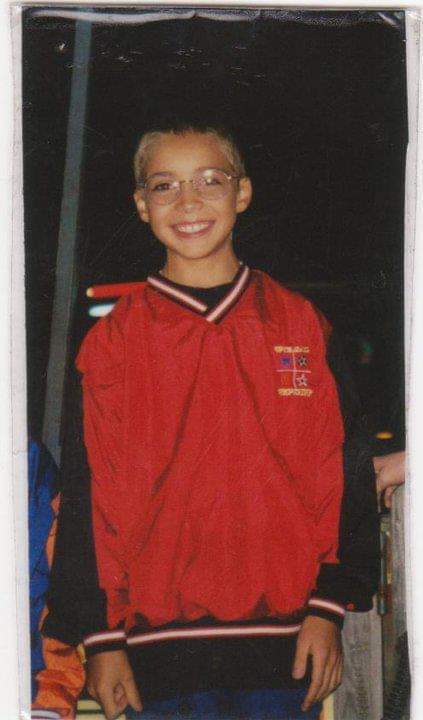

I realized that day that while all music has a purpose, Bach�s music doesn�t even need to be listened to. It is simply absorbed by the soul, whether one is awake or asleep, sedated or alert, and weaves itself in with the gossamer threads of a person�s life. That�s what it did for my son, who was made up of pranks and laughter, Legos and love, art classes and courage � a kind and generous spirit with a really impressive golf swing. But mostly, and maybe most importantly, he was made of really beautiful music.

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �

MaryAnn Zima spent many years editing in Washington, D.C., then returned to the Cleveland area with Johnny to be near family. Luckily, she now lives in Ohio’s wine country.

Leave a Reply